The Same Play in Three Acts

From social media to opioids to AI: a personal reckoning with American innovation

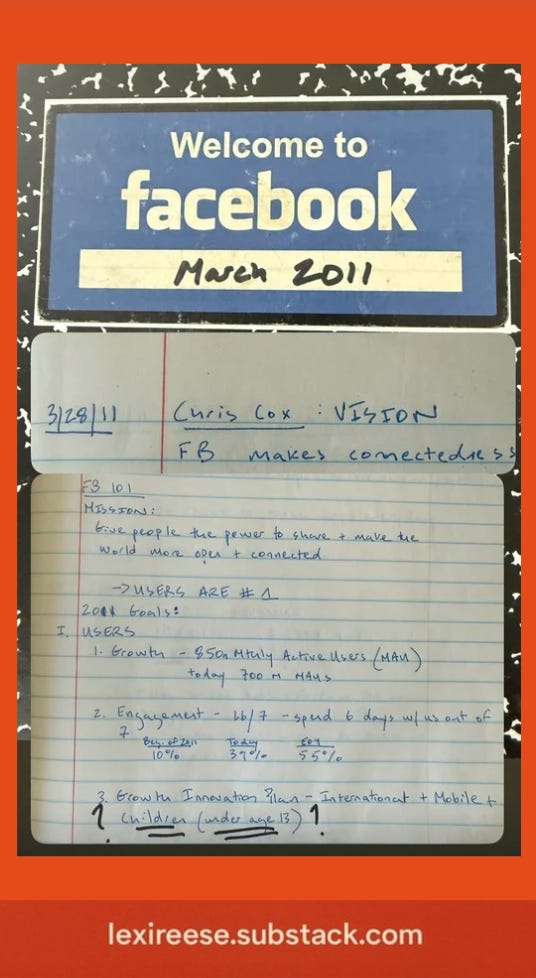

There's a moment in spring 2011 that I keep returning to. I'm sitting in a Facebook conference room with 29 other new hires, many poached from Google where I had come from, listening to Mark Zuckerberg explain how we're about to remake human civilization.

Not improve it. Remake it.

This wasn't your typical corporate onboarding. Chris Cox, running product at the time, opened with media theory—Marshall McLuhan's work on how communication shapes society. Facebook wasn't just another startup. It was the next evolutionary stage of human connection.

When Zuckerberg entered, the vision crystallized. I still have my notes from that day. The mission statement: "Give people the power to share and make the world more open and connected."

The goals were breathtaking in their scope: get people to spend 6 out of 7 days on Facebook. Expand to children under 13 (yes - for real). Double revenue to $3.2 billion in six months.¹

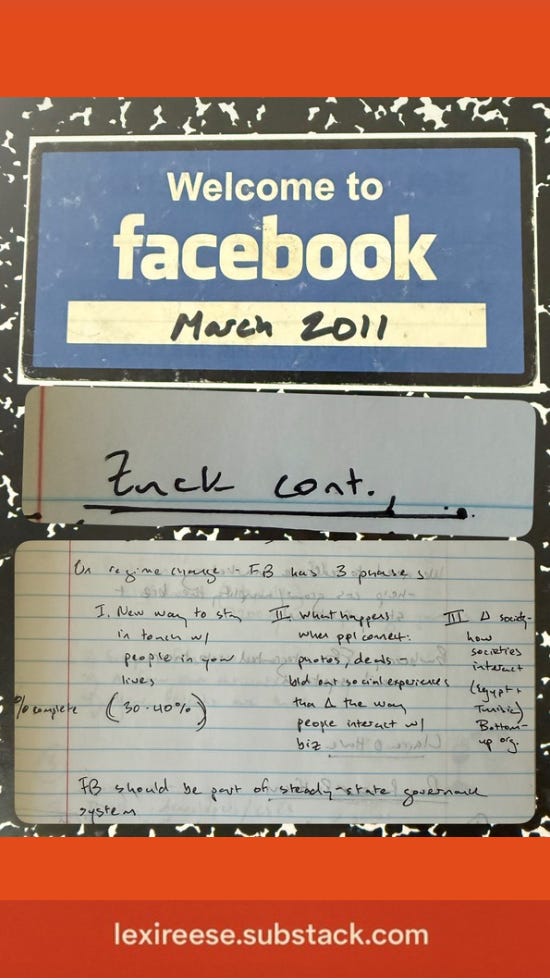

But here's where it got interesting. Zuckerberg started talking about governance. Not corporate governance—societal governance. Facebook would enable "bottoms up" accountability. He pointed to Egypt and Tunisia, where the platform had just helped topple dictatorships.

"Facebook should be part of a steady state governance system," he said, eyes bright with the conviction of someone who'd cracked humanity's code.

The room was electric. This was bigger than business. This was world-changing stuff.

Then Zuckerberg asked us: "Do you think radical transparency is the future?"

Twenty-nine hands shot up enthusiastically.

I raised mine slowly. To disagree.

"I actually think privacy is important," I said. "People should be able to keep parts of themselves to themselves."

The silence that followed was the kind you hear right before someone gets voted off the island.

It was like being the Kristen Wiig character in Bridesmaids—a simple observation met with blank stares and whispers. The whole thing felt more ick than revelation. Here was a guy who'd started Hot or Not in his dorm room, now speaking like a tech messiah. It felt phony, but people were buying it.

So I left after six months.

At the time, I thought I was just witnessing garden-variety Silicon Valley hubris. I didn't realize I was seeing the opening scene of a pattern that would repeat twice more—with increasingly catastrophic results.

Act I: Connection as Conquest

Let's give Facebook credit where it's due. The platform delivered exactly what it promised. Old friends reconnected. Social movements organized. Information democratized. The Arab Spring was real.

But so was everything else.

Facebook's vision of becoming "part of a steady state governance system" came true—just not the way Zuckerberg intended. The platform didn't create more democratic accountability. It replaced democratic accountability with algorithmic manipulation disguised as personal choice.

The numbers tell the story. Internal Meta documents revealed that one in three teen girls said Instagram worsened body image issues.² The 2025 Surgeon General's Advisory concluded: "We cannot state that social media is sufficiently safe for children."³ Yet 95% of teens use these platforms.⁴

Here's what makes this particularly perversely effective: the benefits never disappeared. The harm and the good weren't contradictions—they were features of the same system optimized for one thing above all else: engagement.

Whether that engagement was positive or destructive was beside the point.

Act II: Relief Becomes Ruin

But let's rewind to the 1990s, because this play actually started earlier than I realized.

The promise this time: the end of human suffering. Pharmaceutical companies had developed synthetic chemistry that could eliminate physical pain for cancer patients, accident victims, anyone in agony.

The innovation was miraculous. The need was overwhelming. The initial benefits were undeniable.

Enter Purdue Pharma, deploying OxyContin with the same messianic certainty as Facebook—convinced they were ending human suffering. They told the FDA the drug was less addictive. They told doctors addiction risk was "less than one percent."⁵ Both claims were based on essentially no long-term safety data.

The market responded predictably. Prescriptions exploded from 316,000 in 1996 to over 14 million by 2001. Sales surged from $44 million to nearly $3 billion.⁶

Then came the cascade: prescription opioids created widespread dependence, people transitioned to heroin, fentanyl arrived—50 to 100 times more potent than morphine. From 1999 to 2020, approximately 565,000 Americans died from opioid overdoses.⁷

My brother Peter was among the casualties, though his death doesn't appear in those statistics. He died in a halfway house in a community devastated by fentanyl—one of those externalized costs Purdue never calculated.

Peter had gotten clean and was helping others do the same. He died of heart failure at 48. The police immediately declared it an overdose and closed the case. No investigation. No evidence. They simply assumed—because of where he lived, because of how he'd struggled.

A private investigator we hired later confirmed: heart failure, not overdose. But Peter had already been disappeared by a system that couldn't be bothered to investigate accurately.

This is how profitable harm compounds: companies make billions creating crises, then the communities they devastate get blamed and erased.

Act III: Intelligence Without Wisdom

Which brings us to today's performance: artificial intelligence.

I'm now CEO of an AI governance company, watching enterprises deploy dozens of AI tools they can't track or govern. Legal departments are feeding confidential contracts into public language models. Engineers are shipping AI-generated code to production without review.

Here's what genuinely excites me: AI could democratize expertise that's been rationed by wealth for centuries. One doctor can only see so many patients. One lawyer can only review so many contracts. AI could make high-quality healthcare, education, and legal advice abundant instead of scarce—lowering costs while potentially increasing quality.

But here's what keeps me up at night: We don't understand what we're building. When AI systems get better at math, their writing spontaneously improves for reasons nobody can explain. We're deploying cognitive technologies we understand about as well as we understood the human brain in 1950.

We're automating away the entry-level work that teaches people professional judgment. Document review, first drafts, basic research—these aren't just tasks. They're how people learn pattern recognition, understand constraints, develop strategic thinking. As I detailed in The $11 Trillion Question: Will You Have a Job in Three Years?, this labor disruption could dwarf previous economic transitions.

Meanwhile, we have this surreal mismatch: 7.4 million job openings and 7.2 million unemployed people.⁸ It's like having 7 million keys and 7 million locks where none of them fit. The jobs require data science skills. The unemployed are former retail managers.

And here's the kicker: the Trump administration just released its "Winning the AI Race" plan. As I analyzed in my recent piece, the most telling detail isn't what it prioritizes—it's what it eliminates. In a word: guardrails.

The Script That Never Changes

Each act follows an identical script:

Genuine innovation solves real problems

Messianic conviction eliminates normal safeguards

Rapid deployment externalizes costs

By the time harm becomes undeniable, the technology is too entrenched to regulate

This is what happens when we confuse technological capability with moral authority. The builders genuinely believe they're solving humanity's fundamental problems. This sincerity becomes dangerous because it justifies eliminating traditional checks and balances.

When you believe deeply enough in your mission, democratic accountability starts to feel like bureaucratic obstruction.

The benefits aren't fake. They're just temporary compared to systemic costs that compound over decades.

Why We Keep Buying Tickets

So why does this keep happening? It's not about bad people. It's about bad incentives.

Capitalism runs on quarterly earnings. Every 90 days, CEOs get judged on growth metrics. Long-term risk assessment? Not so much. Democratic stability? Even less.

The companies that grow fastest get the most investment. They use that money to fund politicians. Those politicians protect them from regulation. Rinse and repeat.

We broke the information ecosystem with social media. We broke communities with opioids. We're about to fundamentally reshape how humans think and work with AI.

Each wave hits a society less equipped to respond thoughtfully. Social media fractured our discourse. Opioids destabilized our communities. AI threatens to disrupt our economy while we have less institutional capacity than ever to manage the transition.

Here's the deeper pattern: James Madison wrote in Federalist 51: "If men were angels, no government would be necessary."⁹ The founders understood something crucial: human nature—self-interest, short-term thinking, profit maximization—doesn't automatically align with collective welfare.

This is why we have governance: to check instincts that don't favor societal welfare. Facebook's vision of being "part of a steady state governance system" was the opposite—industry eliminating checks on its own power.

Adam Smith, the supposed patron saint of free markets, warned that when people "of the same trade meet together, even for merriment and diversion, the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public."¹⁰

He saw this coming 250 years ago.

Rewriting the Script

Here's the thing about recognizing patterns: you can either curl into the fetal position or realize how much power you actually have.

I used to think these were separate crises—tech monopolies over here, pharmaceutical scandals over there, AI risks somewhere else. But they're connected by a single thread: us.

Facebook figured this out first. In that 2011 orientation, they explained their core insight: people are the organizing principle. People telling stories, sharing content, influencing each other—that's what changes hearts, minds, and actions. That's what drives their entire business model.

Every industry in this story depends on the same three things: your attention, your treasure, your talent. Social media platforms need your time scrolling. Pharmaceutical companies need your purchases and prescriptions. AI companies need your data and adoption. Politicians need your votes and donations.

If you withdraw any of these—time, money, work, votes—you take away what they need to exist.

This isn't about becoming a digital hermit or abandoning beneficial technology. AI really could democratize expertise, help solve climate change, and augment human capabilities in remarkable ways. It's about being intentional with your choices.

Pay attention to how companies talk about their technology. Do they acknowledge risks alongside benefits? Do they have actual safeguards, or just marketing speak about "responsible AI"?

Notice how politicians discuss regulation. Do they understand the technologies they're governing? Can they explain what went wrong with previous waves of innovation?

Trust your instincts when something feels off. That messianic certainty I witnessed at Facebook—the sense that questioning the vision makes you the problem—is a red flag worth heeding.

We've watched the same play performed three times now, each with higher stakes. Social media taught us that connection without accountability becomes manipulation. Opioids taught us that innovation without oversight becomes catastrophe. AI will teach us about intelligence without wisdom—unless we choose differently.

The question isn't whether AI will transform society—it already is. The question is whether that transformation makes life better for everyone or just concentrates power among those who deploy technology fastest.

We know how this play ends when we just sit in the audience. This time, we can choose to rewrite the script.

The window is closing fast. But you still have power. Use it.

Lexi Reese is the CEO of Lanai, the Enterprise AI Observability Platform. They've developed the first AI Visibility Agent that helps companies see, secure and scale AI safely. She's also a former candidate for U.S. Senate from California.

Footnotes:

¹ Facebook internal projections, spring 2011 new hire orientation materials

² Frances Haugen testimony to Congress, October 2021; Internal Meta research documents

³ U.S. Surgeon General's Advisory on Social Media and Youth Mental Health, 2025

⁴ Pew Research Center, "Teens, Social Media and Technology 2024"

⁵ Purdue Pharma FDA submission documents, 1995-1996; Sales representative training materials

⁶ DEA data on OxyContin prescriptions 1996-2001; Purdue Pharma financial filings

⁷ CDC National Center for Health Statistics, "Drug Overdose Deaths in the U.S. 1999-2020"

⁸ Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, December 2024

⁹ James Madison, Federalist No. 51, February 8, 1788

¹⁰ Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book I, Chapter X, Part II, 1776

This eerie marriage of messianic thinking and tech innovation has many other examples. For just one example - Leo Szilard, who cosigned with Einstein the letter to Roosevelt urging the development of the atomic bomb, was a fervent devotee of HG Wells' messianic vision of science as humanity's savior. And there's ample historical evidence that the bomb's inventors were fervently convinced that they were doing sacred work, not only to defeat Hitler but to usher in a world beyond further war.

One further thought, triggered by your courageous Facebook meeting comment about the need for privacy.

In a manufacturing economy, people deposit money into banks which the banks then aggregate and lend out to industrialists to build the factories that produce material goods.

Since World War 2 we now can produce far more than enough material stuff. But happily, after a brief panic, business reframed the problem – “OMG, we’re producing way too few consumers!” And the feedstock for producing consumers is attention. So now in our consumer economy, people are persuaded/hypnotized/coerced to deposit their attention into media, which then aggregates it and lends it out to businesses to create consumers.

So I say to my meditating friends - your practice of meditation is not just "spiritual" (whatever that means). It can also be a personal act of resistance to the economic system and the political system that supports it– because it’s the essential step in learning how to re-own, anchor and direct your own attention rather than have it sucked out of you 100 times a day and used by others to advance their interests rather than your own.