When I was four and someone stole my golden Easter egg, I was inconsolable. Not just about the chocolate—though that mattered too—but about the fundamental unfairness of it all. Peter didn't lecture the kid or make a scene. He just went and got it back. The world, briefly, made sense again.

That was Peter: he saw when someone needed help, and he helped.

^ Peter consoling yours truly

He and my sister were especially close. There's a story—I'm not sure who saved whom—but one of them fell into a pile of ground bees, and the other went in after them. That's how they were with each other. That's how they were with me. They looked out for people. My sister still does.

^Pete and My Sis

Peter carried this into everything he did. He worked at a home for at-risk youth in Atlanta, going into abandoned houses in dangerous neighborhoods to reach kids everyone else had given up on. His supervisor said he was the only person willing to do that work. He counted homeless people on the streets, not for some bureaucratic report, but because he believed each person mattered enough to be counted.

In 2012, Peter's daughter was born. He named her after our mother, and he thought she hung the moon. When he had his little girl, his incredible wife, and our mom around him, Peter seemed genuinely happy. Fulfilled in a way I hadn't seen before.

^ Pete and his *supercalafragalistic* daughter

He'd discovered a kind of love that surprised him with its intensity—but I think that intensity came with a fear of not being able to hold it together. The same fear all of us parents feel of not being able to protect our children. For Peter, who felt everything so deeply, that fear created the conditions for addiction's claws to grab him again.

When addiction returned—and he lost his wife and little girl as a consequence—he went to the darkest place he'd ever been.

Peter died in 2017 at forty-eight—heart failure, in a halfway house in a neighborhood where such deaths don't warrant much investigation. The police didn't look into it. They assumed drugs, despite no evidence and everyone saying he was clean. I learned about invisibility viscerally then, watching how quickly the system decided what kind of person he must have been based on where he died and how he'd struggled.

But the system wasn't the only one who made Peter invisible. I did too.

I had followed advice from Al-Anon: "Detach with love." For the last two years of Peter's life, I had no contact with him. Two entire years. He was on the street for some of that time. People want to tell me that's okay, that I had to protect myself. It's not okay. It's the biggest regret of my life.

The irony was devastating: a man who spent his life seeing people others had stopped seeing became invisible himself the moment he died.

At his memorial service, the kids from the group home said "Mr. Pete always told us to live up to our potential." They built a garden shed with that phrase on it and sent belloons into the sky with messages to him. He would call them day and night, they said. He was always available. He was like a brother to them.

I've been thinking about Peter because today is his birthday. And I've been considering what we call "bro culture" now. The term has come to mean something ugly: chest-thumping dominance, the celebration of cruelty, an obsession with winning that transforms every interaction into conquest. It's become synonymous with a particular kind of masculinity that values accumulation over connection, performance over presence.

But that's not what Peter taught me about being a brother.

Where contemporary masculinity seems to celebrate emotional numbness, Peter felt everything. Where it prizes individual achievement, he created connections. Where it demands constant performance, he was content to be present. He made art. He noticed when people were hurting. He understood that strength and tenderness weren't opposites.

When I had a messy, embarrassing breakup and did something spectacularly stupid, Peter was the first to remind me that we all do stupid things. He made it into a joke, suggesting I needed to do more of them to take some heat off him with our parents. We fought, the way siblings do. But underneath the arguments was something steadier: the knowledge that we'd show up for each other when it mattered. He always did.

Peter was an artist who felt things so deeply that other people's pain became his own. In an age when we're often scrolling past suffering—children in war zones, systemic cruelty, the daily brutalities that fill our feeds—Peter couldn't manage the emotional compartmentalization that modern life seems to require. He carried it all, and when the weight became unbearable, he sought relief in the only way he could figure out how.

Real fraternal love isn't about dominance. It's about reliability. It's about using whatever power you have to make the world a little safer for people who need safety. It's about showing up, again and again, even when—especially when—it's inconvenient.

The question that matters isn't whether you're male or female, liberal or conservative. The question is whether you see suffering and try to alleviate it, or whether you see vulnerability and try to exploit it. Whether you use your strength to protect or to dominate.

Peter knew the answer. He lived it every day—in broken houses, on Atlanta streets, with kids who needed someone to believe in them. He understood that being a brother means being available. Being willing to see people others have stopped seeing. Being strong enough to be gentle.

When people ask why I care so deeply about ensuring others feel seen and heard, I think of Peter—not only because he taught me what such seeing looks like, but because I failed to see him when he needed it most. Because I watched him become invisible to the systems that should have valued his life, and because I made myself invisible to him when he was drowning.

That regret drives much of what I do now. It's not noble motivation—it's just what's left when you realize you let someone you love disappear while you were supposedly protecting yourself.

Imagine if we all looked out for each other the way Peter and my sister looked out for me, the way Peter looked out for those kids. Imagine if our systems worked that way too—if they saw people clearly instead of writing them off, if they investigated deaths instead of assuming, if they counted everyone as fully human.

In Pete’s memory, I'm choosing to believe that real brotherhood—the kind that sees, that shows up, that fights for people when they become invisible to power—isn't gone. It's just been overshadowed by people who've stolen the language while abandoning the practice.

Real brothers don't build walls. They go through them to reach people on the other side. They don't dismiss pain. They get your Easter egg back. They don't write people off. They tell them about their potential and stay available to help them find it. They don’t disappear people at traffic stops, in their homes, at Home Depots. They put their bodies between masked guards and the victimized, demanding that humanity and justice prevail.

That's the kind of brotherhood worth remembering. That's how we honor Peter, and everyone who needs someone to see them clearly. That's how I try to live with the weight of those two lost years.

I love you, bro.

Peter Hust

June 8, 1969 - 2017

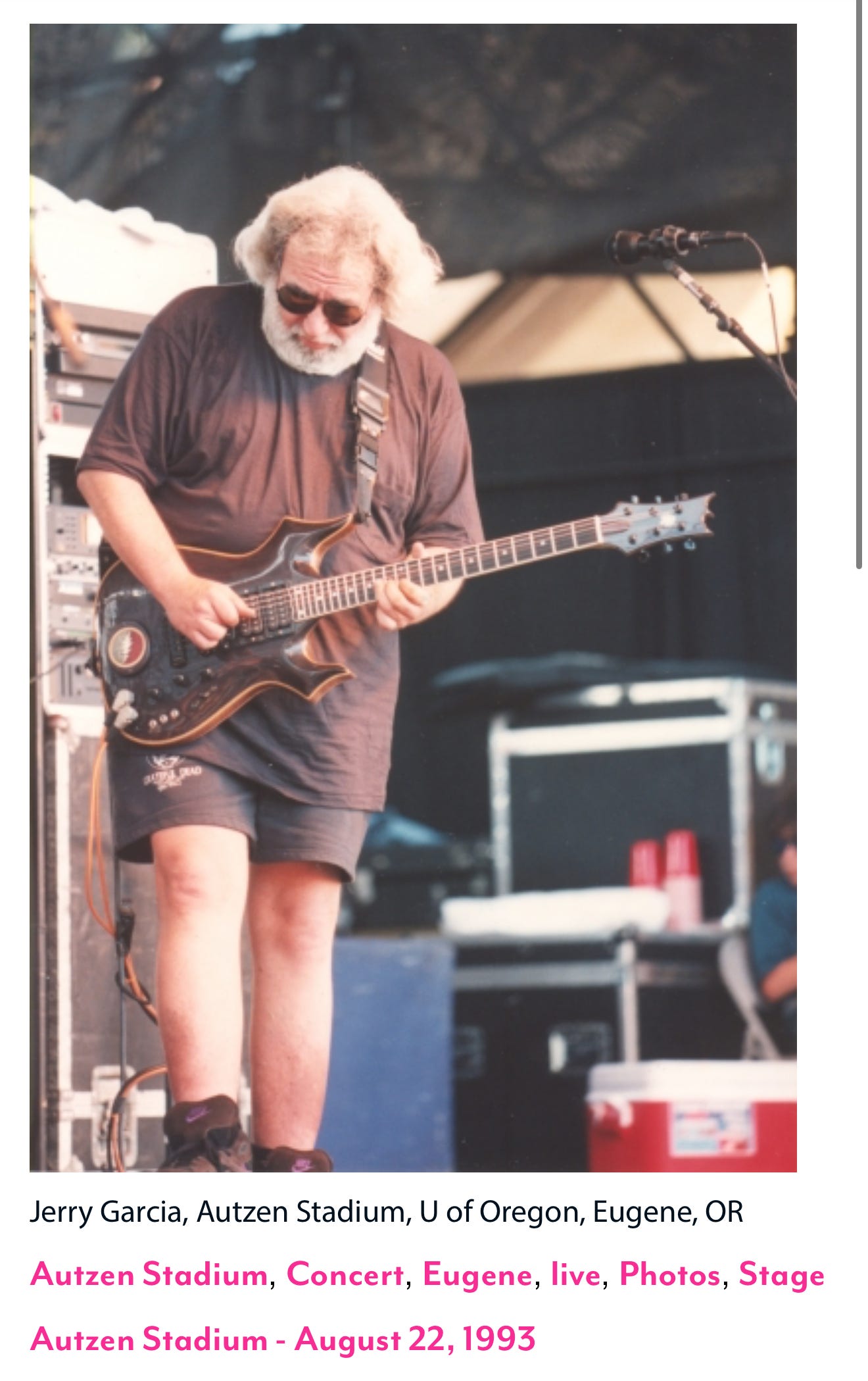

P.S. Listening to Ripple and remembering Eugene 1993 when we caught a glimpse.

If my words did glow with the gold of sunshine

And my tunes were played on the harp unstrung

Would you hear my voice come through the music?

Would you hold it near as it were your own?

… Reach out your hand, if your cup be empty

If your cup is full, may it be again

Let it be known there is a fountain

That was not made by the hands of men

There is a road, no simple highway

Between the dawn and the dark of night

And if you go, no one may follow

That path is for your steps alone

… If you should stand then who's to guide you?

If I knew the way I would take you home

Beautiful. I remember Peter taking me under his wing way back in the day. He was a gem and I’m so glad for this glimpse into who he was later on, thank you. May his memory continue to be a blessing. Much love.

No doubt Peter would be proud of you Lexi. Thank you for all you have done for Freya and I, and for so many others. Your altruism and actions put you in a very elite class. I will light a candle for him later on.